Britain’s military friendship with Norway goes back a long way. In World War I the government was officially neutral, but it permitted Britain to control its merchant fleet, which suffered badly from German U-Boat attacks. Norway also supported our army fighting for Russia’s white government, after the Bolshevik government made peace with Germany. In World War II, we failed to prevent Hitler’s troops from taking over the country, but the King and many Norwegians were very much on the side of the Allies.

Although there has been some economic rivalry over North Sea resources (oil. gas and fish), it is good to see that the maritime alliance has blossomed recently. Today’s announcement of a deal to supply the Norwegian Navy with at least five new frigates is not only good for the bank balance, but it is also tremendous news for NATO.

My first task after joining my regiment was a three month NATO winter deployment to northern Norway, where I patrolled inside the Arctic circle close to Russia in our light tanks. I have never experienced worse conditions than on Hjerkin Ranges. The weather was especially cruel on the Royal Marines, who suffered multiple cold injuries with many of them have to be flown back to England for medical treatment. From my perspective, the lessons our wonderful Norwegian army liaison officer taught me about surviving in the cold were some of the most important in my life. If the worst happens and we end up in a fight with Russia, I know that we will be able to rely on the Norwegian Armed Forces and with this new contract, protect the vital waters of the North Atlantic.

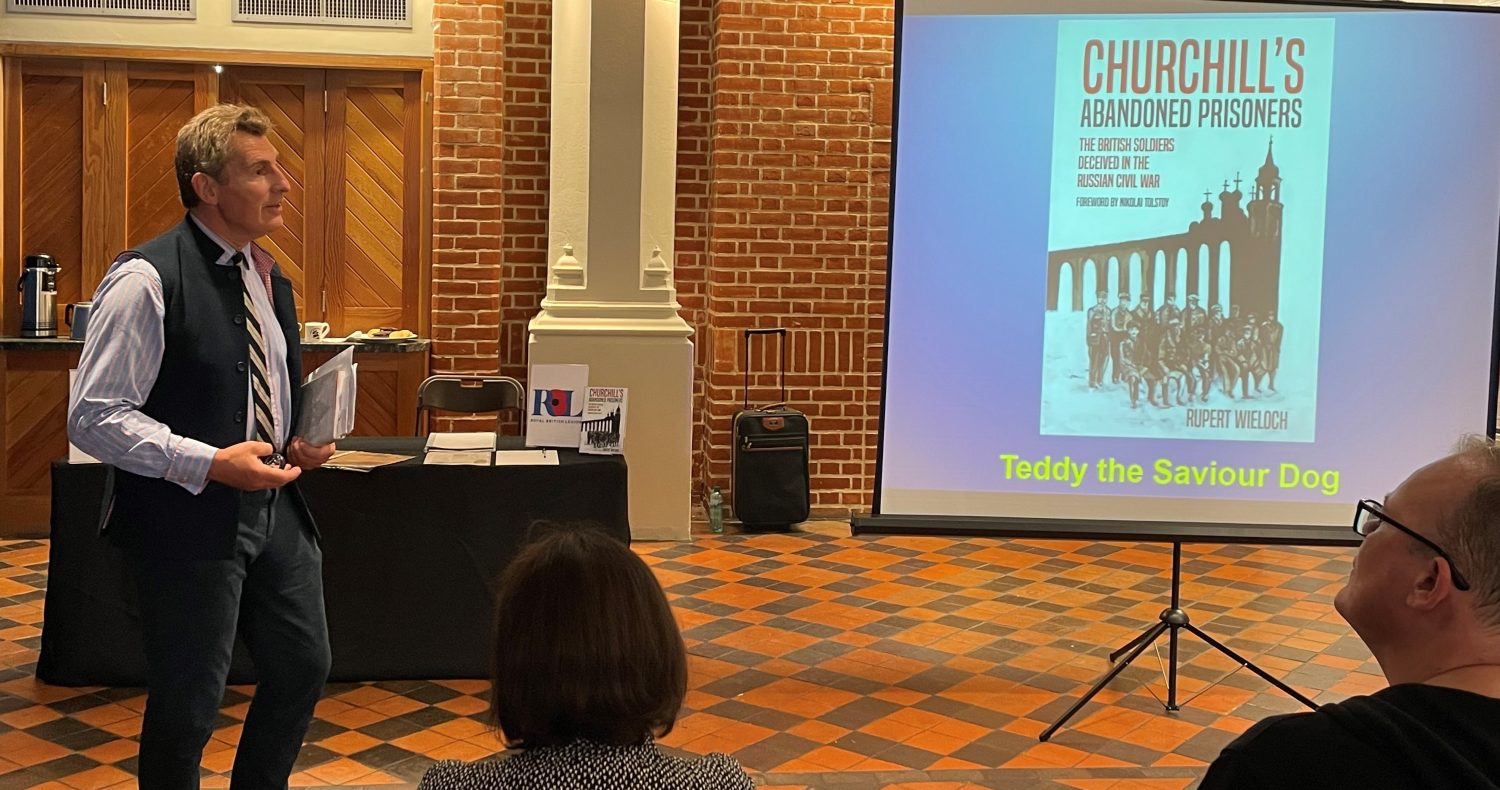

Trialling Winter Camouflage in Norway 1980