One of the big puzzles about the British involvement in Siberia in 1918 is whether there was a higher purpose than defeating Prussia and helping those who had fought on the Eastern Front. The initial British reconnaissance mission, led by Colonel Josiah Wedgewood DSO, recommended that any involvement to assist the British refugees fleeing from the Red Terror should be conducted through the formal Anglo-Japanes treaty. The subsequent landing of a Royal Marine detachment (under Japanese command) to facilitate this humanitarian assistance and the arrival of a further scoping mission led eventually to a medium scale operation, which was divided into six parts: logistics (delivering millions of tonnes of war equipment to the White Army); medical (assisting in countering epidemic typhus); the railway mission (helping to secure and operate the Trans-Siberian Railway); training (in military acadamies, schools and formations such as the Jaeger Artillery Brigade and Anglo-Russian Infantry Brigade); fire support (such as the Royal Navy Guns commanded by Tom Jameson on the Kama river); and military intelligence.

Given the scale of the campaign, it is not surprising that some academics have suggested that there was a higher purpose to separate Siberia from Russia, but I have found little material in London archives to support this theory. There is much more evidence to suggest that the higher purpose was the same reason that the West now supports Ukraine in their efforts i.e. the British government’s hatred of military authoritarianism. They knew about this state of affairs because several Russian and British liaison officers, who served together on the Eastern Front, were involved in the Siberian Military Intelligence mission.

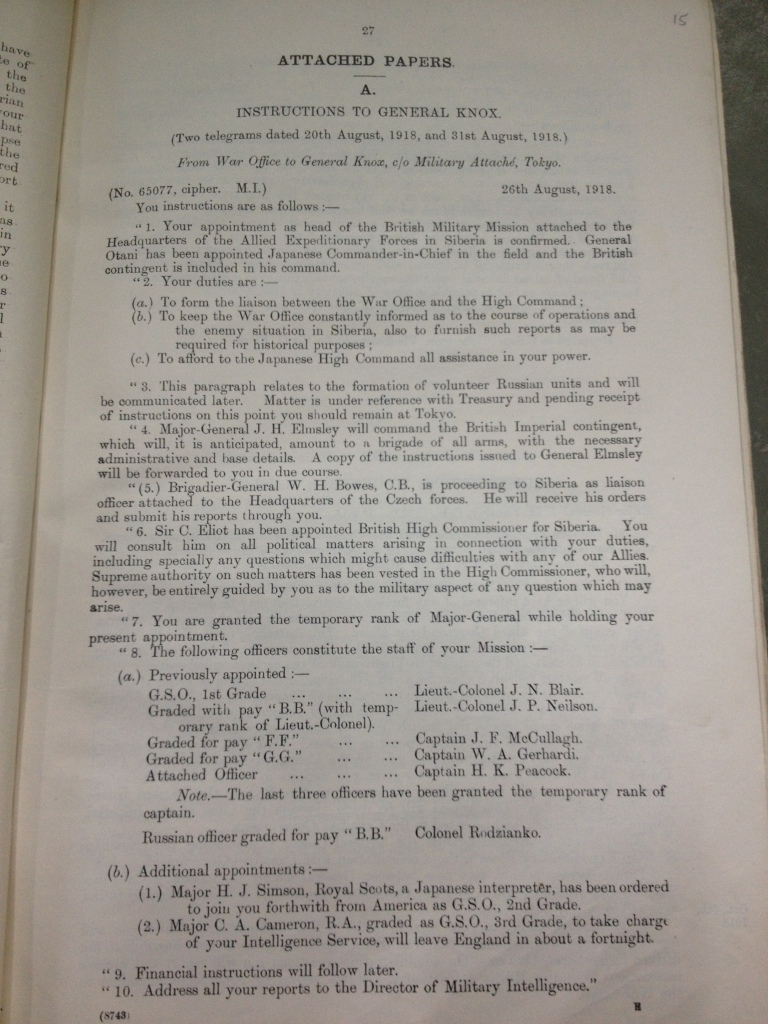

The MI imperative can be seen from the instructions to the Senior British Military Commander, Major General Sir Alfred Knox, which are shown in the document below. This reveals that the first group of British officers to travel to Siberia included three Russians: Henry Kartchkal Peacock had lived in Siberia for eight years and was well-versed in its culture (he was awarded an MBE in the Siberian Honours); William Gerhadi (awarded an OBE for his work as Knox’s aide), was later described by Evelyn Waugh in the highest terms: “I have talent, but you have genius”. The third member of this group, Captain Leo Steveni (awarded an OBE in the Siberian Honours), arrived in May and was already working with the White Russians when this document wes sent. Steveni’s unpublished memoir in the King’s College London Liddell Hart Collection was a vital source for my book.