As I wait patiently in Sri Lanka for a return flight to Blighty, I am seized by this question about the efficacy of soft power. A major part of the Strategic Defence Review in 2010 centred on Defence Diplomacy. The buzz words were “Down Stream Conflict Prevention”, which translated to a range of confidence-building initiatives from disarmament to deployed training assistance teams. However the Down Side was less hard power with huge cuts to the Army to pay for two new Aircraft Carriers and the supporting fleet ships (which have played no part in the latest Middle East crisis).

The prognosis is not good. Hard power is still King, with the advocates of soft power looking impotent. The key tenets of the Geneva convention and other military law books have been shredded. The UN’s agreed rules (minimum force, self-defence, impartiality and consent) have been ignored. And yet, through it all, HM King Charles III has today highlighted a soft power international institution of 56 member nations that has lasted the test of time and still speaks as a Force For Good.

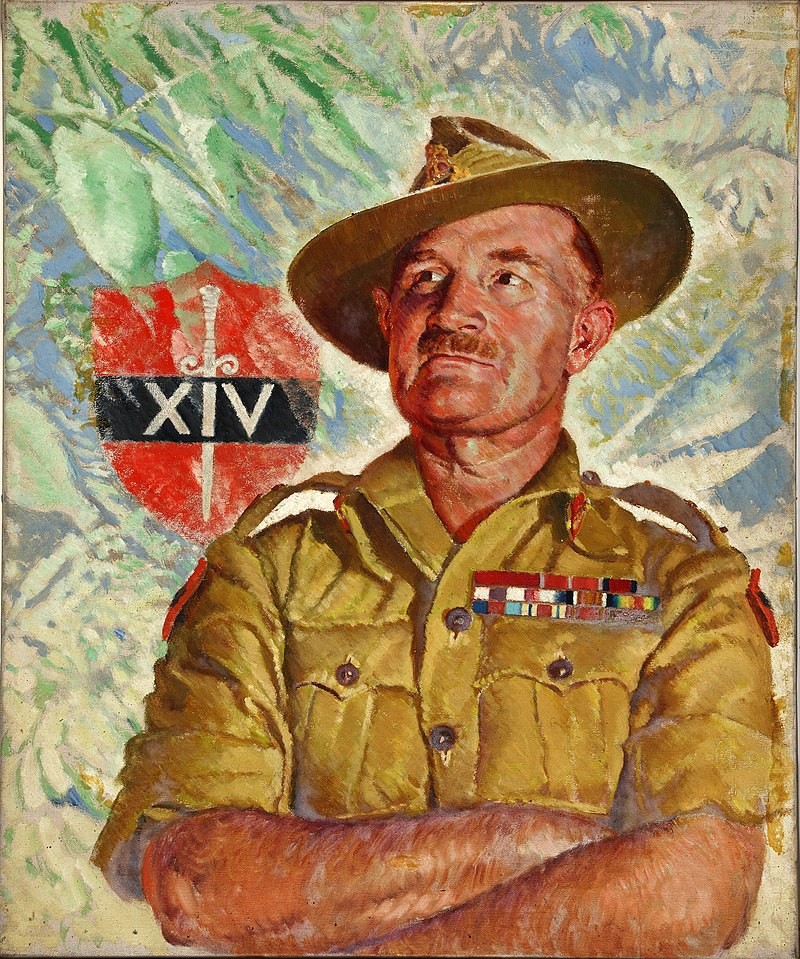

Sri Lanka this week has epitomised the spirit of the Commonwealth by responding to a humanitarian SOS, while maintaining its independence and neutrality. I have found that Sril Lankans are immensely proud of their heritage, whether that is the ancient influences, or the Dutch, Potuguese and British eras. They stopped the Japanese advance after Hong Kong and Singapore surrendered in World War II and have very effective Armed Forces. But, as they raise their flag here each morning, they also act as a beacon to others by saying “don’t give up on soft power”.