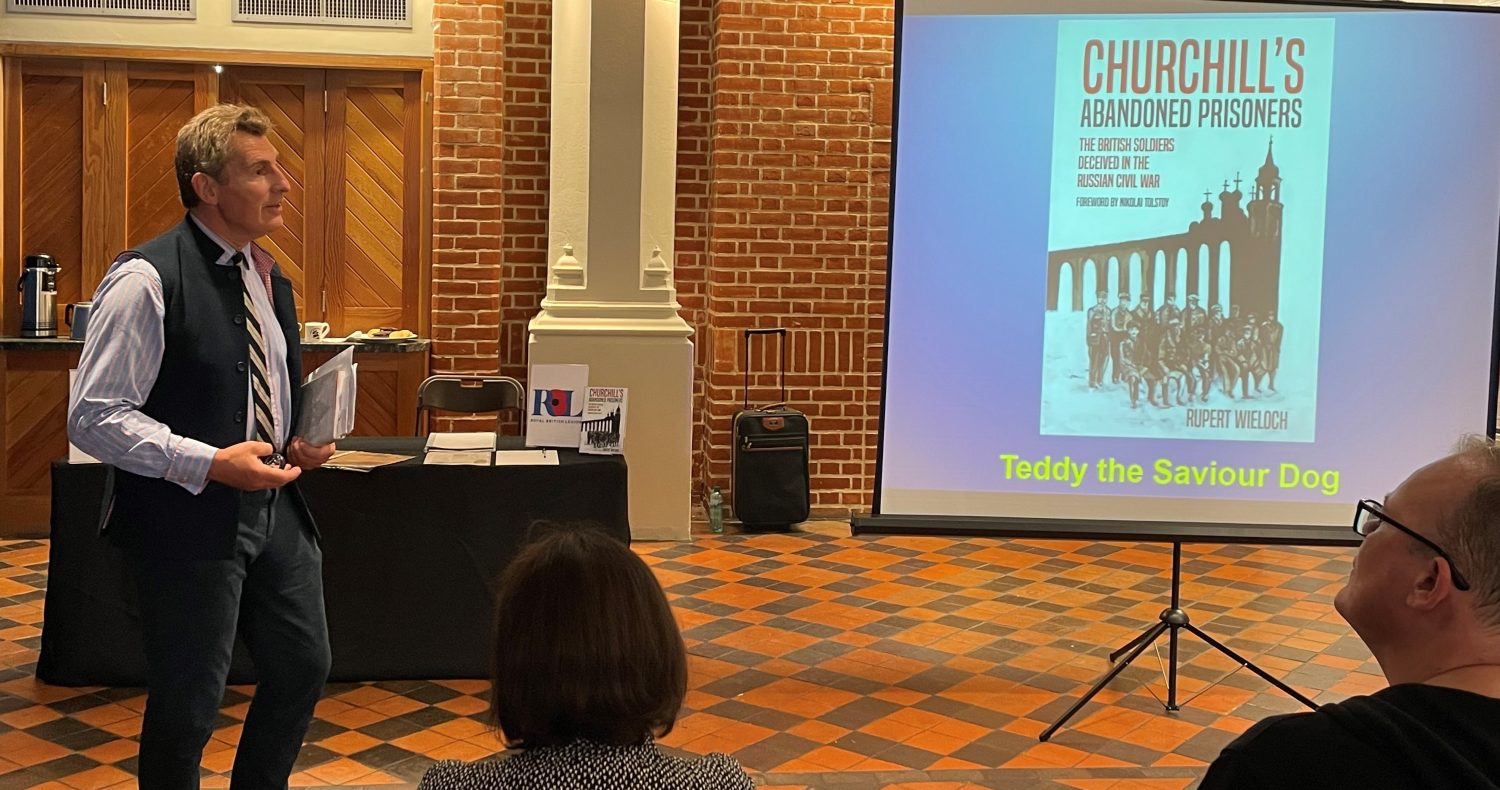

When I give my talk about the state of the British Army in August, one of the important topics will be our battle equipment, including the new British tank, named Challenger 3.

I had the honour of operating all the different types of British tanks in service between 1970 and 2020. These included the lightly armoured Saladin, Scorpion and Scimitar (all of which were manufactured by Alvis) and the heavily protected Chieftain and Challenger Main Battle Tanks with their 120mm rifled-bore main armament. Perhaps more importantly, I held the appointment of Head of Defence Equipment Reliability, when our new British tanks were conceived, assessed and designed.

Designing a tank is like playing rock, paper, scissors. It is a balance between firepower, mobility and protection (or survivability). Users who desire perfection will only be frustrated because compromises have to be made; for example, if you increase the calibre of gun, or weight of armour, the tank may end up as a slow, sitting target. So, it is not surprising that the new British tank is closely related to the old British tank with the same hull but a new turret, active protection system and (smooth-bore) gun. For traditionalists, it is sad to see that we are buying a German tank and that the gunnery skills will be diminished, since we will no longer be able to accurately shoot High Explosive rounds beyond two miles.

Fighting Vehicle 4201 Mark 10 Chieftain with Improved Fire Control System